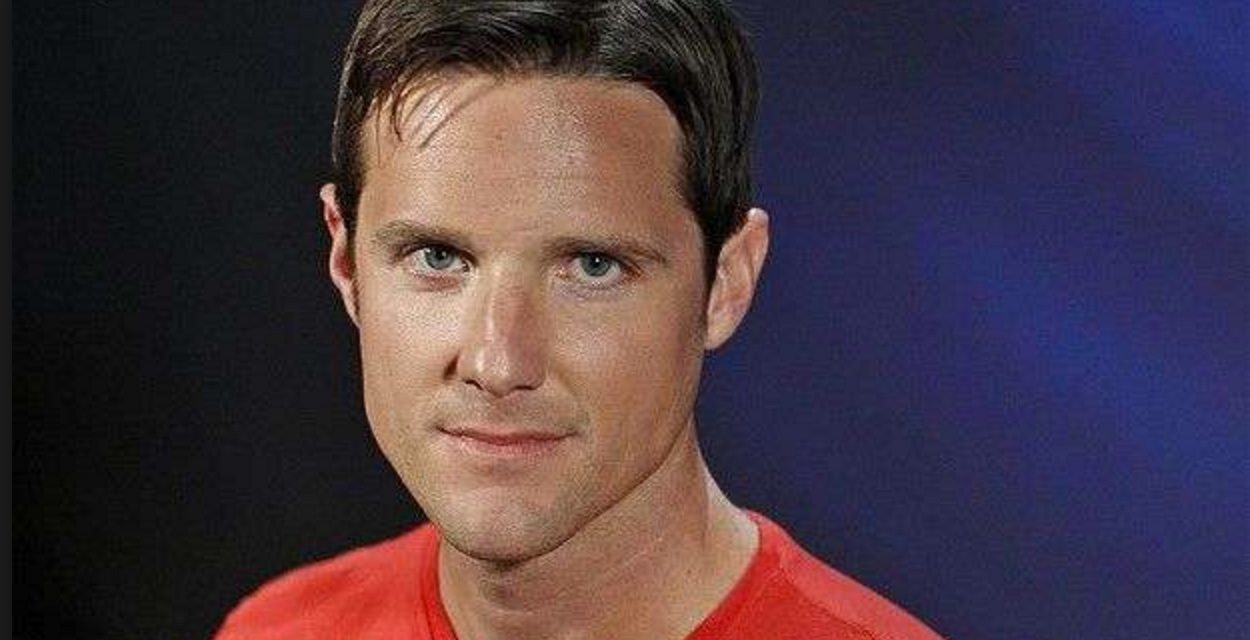

With news breaking last Thursday that Invisible Children co-founder, Jason Russell, was detained after freaking out in San Diego and treating passersby to an excellent view of what we might tactfully term his “Joseph Kony”, it seems like the right moment to take a step back and assess the whole “Kony 2012” phenomenon. Are campaigns like this the way to tackle major issues?

A quick recap: “Kony 2012” is a 30-minute video about the activities of the LRA – the Lord’s Resistance Army – in Central Africa. The LRA, headed by Joseph Kony, is “accused of recruiting children into sexual slavery and using them to wage a violent campaign to topple Uganda’s government.” Russell’s charity, Invisible Children, made the video with the clear aim of mobilizing public opinion in the US and Europe against the LRA and, specifically, against Kony. The video is highly emotive, light on fact and heavy on Russell, who narrates and also uses a conversation with his own son to illustrate what he feels to be the moral issues at stake.

This isn’t the first time a documentary maker has taken centre stage in his own work – Michael Moore is famous for it – and it’s not the first time a charity has applied a steely grip to our heartstrings in order to get its point across. But “Kony 2012” is the first time a charity has expressly used social media to orchestrate a campaign, putting the video out on YouTube and urging viewers to use Facebook and Twitter to pass the message along.

As a strategy it seemed to work brilliantly. Within hours of its posting, the usual social media staples – photos of cats in jars or pictures of sunsets with inspirational quotes – were pushed aside as people fervently posted and tweeted about a country most of us would be hard placed to find on a map.

The campaign received even more of a boost when the slebs rushed to endorse it. Chief amongst these Angelina Jolie, Goodwill Ambassador for the UN since 2001. Her comments: “I’ve been to Uganda and Congo and been to the International criminal court myself … he’s the one we all want to see in jail, so I think it’s great that more people are talking about it. He’s an extraordinarily horrible human being who, you know … his time has come and it’s lovely to see that young people are raising up as well.”

Young people weren’t just “raising up.” They were raising money too, along with their parents. Invisible Children received $5 million in just 48 hours as a direct result of the campaign.

But how many people actually understood what they were donating that money for? Did Angelina Jolie – with her extensive travel in Central Africa and UN contacts really grasp the issues? Did they know that the LRA has not been active in Uganda since 2006 and that relative peace has returned to this part of the country? Do they know that the Ugandan army, which Invisible Children asks viewers to support, is heavily implicated in exactly the same crimes as the LRA? Do they realise that ordinary Ugandans who have seen the film, see it not only inaccurate, but as an example of neo-colonialism – of white people thinking they understand the problems of Africa better than Africans do themselves?

I’ll bet they don’t. They saw a neatly packaged argument and an easy way to assuage a sneaking western guilt about how the rest of the world has it and clicked a button. Those who argue that – putting the facts aside – the video was a good thing because it raised awareness about an important issue (and this seems to be Ms Jolie’s point too) are also wrong. The video didn’t raise awareness. We already know that Africa as a continent has a host of problems to contend with. We would have to be deaf, blind and mentally challenged not to be aware of the regular conflicts, the famines, the massive displacements. This video didn’t raise awareness, it streaked across our collective consciousness, the same way all internet memes do.

The great irony is that it has been replaced with the images of Russell, naked and gesticulating, on a San Diego street crossing. His breakdown is now the meme-du-jour. No one cares about the child soldiers any more. That’s just so yesterday.

The pity of it is that “Kony 2012” has reinforced the idea that simple solutions can be applied to big problems. Show a film and the pressure mounts on governments to do something. Politicians jump on the small part of the bandwagon not occupied by the slebs. Throw Kony in jail and the fighting in Central Africa will stop. The children will be free. Rainbows and unicorns will rule.

The other unwanted side effect is that now people think they’ve done their bit. They’ve clicked, they’ve donated. Africa is over. Normal service is resumed: cats, sunsets, quotes from the Tai Chi once again populate the timelines. If appeals for help are made again, this time for a genuine emergency – like we’re seeing in Sudan right now – compassion fatigue may have set in.

As Russell capers in the street, by all accounts unhinged by the stress of his success and/or the guilt of his manipulation, I can’t help wondering if it ever occurred to him that when he decided to tap into the power of social media to get his point across, he would turn into an anti-social spectacle, both in the media and in real life.